Use of torture in relation to combatants and irregular fighters

The publication “Torture of civilians” on this website describes the systematic use of torture as a method of violence against the civilian population in the Chechen Republic. The treatment of combatants and irregular fighters did not differ in this respect, and was often exacerbated due to their status.[1]

According to Article 1 of the Convention against Torture,[2] the definition of torture includes four elements:

- Intent;

- Any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person;

- For such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, or intimidating or coercing him, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind;

- Inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

The principles of international humanitarian and human rights law uniformly prohibit the use of torture against both civilians and combatants. The 1949 Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocols (1977); the European Convention on Human Rights (1950); the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984); and other international documents consistently prohibit all forms of torture, including during both international and non-international armed conflicts.[3]

Within the context of armed conflicts, it has not been uncommon for warring parties to seek to “legitimize” the prohibited methods of warfare used during military actions.

For example, on 30 March 2006 at a press conference in Moscow, Chechen President Alu Alkhanov admitted not only to the use of torture, but also the frequency of such incidents in the Chechen Republic. According to him: “Torture during interrogation is used throughout the world. However, in Chechnya, the level of such crimes is two to three percent higher”.[4]

This publication refers to statistics provided by the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center Database (hereinafter the Database) confirming the widespread practice of the use of torture against combatants and irregular fighters during the armed conflict. Often, the practice of torture was also accompanied by other violations. In some cases, however, due to insufficient information concerning the nature of the violation, it was difficult to confirm whether the circumstances did indeed amount to torture. Analysts responsible for registering information in the Database only register violations qualifying as torture on the basis of the most accurate information. In light of this, the following publication is divided into two parts. The first part represents the statistics and accounts relating to victims, as well as the nature of the violations, which allow for precise conclusions to be drawn about the use of torture against the victim. The second part describes violations, which could have been qualified as torture or violations which accompanied torture. Such violations include cruel and inhuman treatment, offences of a sexual nature, murder committed with particular cruelty, beatings and other injuries.

Statistics on the use of torture against combatants and irregular fighters

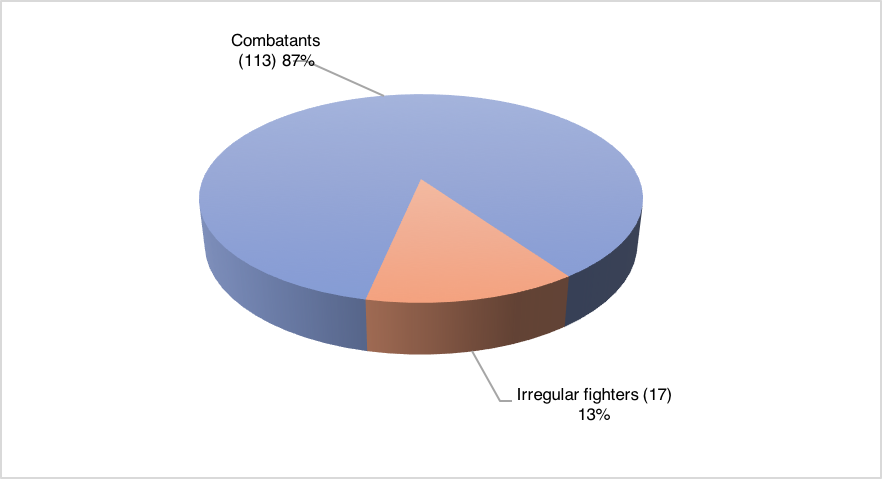

The Database contains information on at least 145 combatants or irregular fighters who were tortured in the context of the conflict in the North Caucasus,[5] 130 of whom were tortured in the Chechen Republic. The majority of these victims in Chechnya (113) held the status of combatants, while the remaining 17 were considered as irregular fighters (chart 1).

The vast majority of the victims in Chechnya (128 victims) were men, with only two women among the victims, both of whom were among other members of the armed forces who surrendered to Russian troops.[6] Like other captives, they were subjected to repeated torture and beatings, inhuman treatment and humiliation.[7]

At least 109 victims were adults at the time of the violation (between 18 to 60 years old) and in 21 cases the age of the victim could not be determined. Among the combatants/irregular fighters there were also victims belonging to vulnerable groups such as: those suffering from sickness (three victims); those with disabilities (two victims); internally displaced persons (one victim); and those in a helpless state (one victim).

In addition to these groups, just over half of the victims (75) were unarmed at the time of the violation, and therefore ought to have been subjected to treatment as established by international humanitarian and human rights law, yet this was not the case. In one such case in January 2000, irregular fighters who were trying to force their way through Grozny, which had been blockaded by Russian troops, were subjected to cruel treatment.[8] Many of the victims were hit by exploding mines while passing through a minefield and sustained severe injuries, following which they were transferred to the local hospital in the village of Alkhan-Kala, the basement of a nearby store, and to several private houses. Later, however, the hospital was cordoned off by federal forces and the wounded fighters who had been taken to the basement of the store were killed. Others who were injured were captured by the military and had their bandages removed, and were transported by bus to a concrete bunker located on the territory of the oil-producing directorate in the village of Tolstoy-Yurt. There, the wounded victims were beaten, tortured, and deprived of food and medical care. According to one of the victims:

I was held in a bunker in Tolstoy-Yurt for six days. They beat me on my wounded leg, and beat me very cruelly. There was no need for an amputation of the leg, but the military had shattered the bone.[9]

As a result of such ill-treatment, more than ten victims died from their wounds and lack of medical care in the bunker; the rest were transported to other places of detention.[10]

Regarding the role and belonging of the victims, 78 belonged to members of the armed forces opposing the Russian Federation; 46 represented the security forces of the Chechen Republic; and six were employees of law enforcement agencies sent from other regions of the country.[11] The vast majority of the victims (114) had their freedom of movement restricted at the time of the violation and thus could not escape the suffering.

In at least 16 cases in Chechnya, torture resulted in the death of the victim. The majority of these victims were members of illegal armed groups who had surrendered to Russian servicemen in March 2000 during the notorious battles for the village of Goy-Chu (Komsomolskoye) in the Urus-Martanovsky District.[12] According to the collected data, those who surrendered were systematically tortured: some were kept in trucks in conditions of extreme overcrowding, they were deprived of food and water, and the sick and wounded did not receive any medical assistance.[13]

The Database also contains information about the deaths of local security forces as a result of the use of torture. In the context of the military conflict, representatives of local law enforcement agencies were placed in a difficult situation as they were threatened by the activities of both irregular fighters and the federal services. The Database describes the case of the death of the head of the local police who was arrested for unknown reasons and kept in one of the Chechen camps.[14]

According to a human rights activist who wished to remain anonymous: “His arms were broken, and his spine was damaged … He died at the end of the month, and his family had to buy his corpse from the Russians.[15]

Among the methods of torture registered in the Database are instances of bone fracturing; scalp removal; severing of ears; removing nails from fingers and toes; use of gas; suffocation; stabbing; deprivation of food and water; use of pliers and fire; and the use of electric currents. Relatives or neighbors of these victims were often punished in a similar manner. For example, on 16 March 2000 in the town of Shali, two members of illegal armed forces, as well as two civilians – the son and brother of one of the suspects – were captured by military personnel. According to locals, all four were taken away and tied to the rear of a UAZ vehicle. The following day, the mutilated corpses of two victims were transported from the commandant’s office for burial. The faith of two civilian victims remains unknown.[16]

The practice by the Russian military of requesting ransom in exchange for the return of combatants or other fighters to their relatives (either dead or alive) was not as widespread as in the case of civilian victims. This is a result of the particular status of the victims which deterred relatives from divulging information. Yet despite this, the discontinuation of the persecution of the victims was not guaranteed. According to a former irregular fighter who was tortured by the military:

“Yes, I was amnestied, my family paid seven thousand dollars for this. But this amnesty means nothing. I am under threat of secondary detention. My relatives have already been told that they are looking for me to arrest”.[17]

As a result, the man was forced to leave the Russian Federation for his safety.[18] In another case, in the village of Alkhan-Yurt, the Russian military severely beat the senior lieutenant of the local security forces, who had intervened and tried to prevent local residents from being robbed. Despite the fact that the lieutenant had managed to buy himself out in exchange for liquor and money, he nevertheless died on the third day following his release.[19]

Statistics of violations which may have qualified as torture against combatants and irregular fighters

As mentioned previously, a number of violations did not squarely fit within the definition of torture due to insufficient information being available, and were consequently registered in the Database as other violations by the analysts. This section describes violations, both mental and physical harms suffered by the victims, which could possibly be defined as torture.

In addition to the above statistics, the Database contains information about the following violations perpetrated against combatants and irregular fighters in Chechnya: beatings or other injuries (64 victims); inhuman or degrading treatment (59 victims); murder committed with special cruelty (31 victims); and sexual offences (one victim). Furthermore, the mutilation of corpses was recorded in 37 cases. The project’s website contains publications which describe in detail some of the violations listed below.

According to the Database, in some cases, episodes of beatings lasted for hours;[20] victims of such treatment were unable to move after or did so with difficulty,[21] and evidence also suggests that the beatings were characterized by extreme cruelty.[22] For example, on 16 July 2000 at five o’clock in the morning in Grozny, a special unit of federal law enforcement agencies detained five individuals, among which were four members of the Chechen police. During their detention, three victims were cruelly beaten and one of the victims had a bloody bandage on his head. The victims were kept in a military camp in Khankala until August 2001 and then taken away in an unknown direction.[23]

The Database also contains information about victims that suffered a “cruel death”[24] or were “brutally murdered”.[25] In the absence of other data, however, such information did not disclose the entire nature of the crimes. There is also information about the beheading of victims, though it is impossible to determine whether the victim was beheaded before or after their death. Among such cases is the murder of a member of the security forces in Grozny. On 17 July 2005, unknown persons drove to the market in Grozny and threw a strange object out of their car. It transpired that this object was in fact a human head attached with a note reading “munapik” (translated from Arabic as “unfaithful”). Servicemen soon arrived and took the severed head with them.[26] Additional information concerning the circumstances of the death of this victim is not available.

Thus, as the statistics of the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center Database reveal, the practice of the use of torture against combatants and irregular fighters during the conflict in the Chechen Republic was – as in the case of the civilian population – widespread and, in many ways, perhaps more exacerbated.

In many cases, torture was used against captured victims who were usually wounded and unarmed. Amnesty was not always a guarantee, as those who were supposedly amnestied were nevertheless subjected to repeated harassment and new arrests. Given the conditions in Chechnya at the time, amnesties had become a mechanism to identify insurgents in order to further repress them in one way or another. Many of the amnestied Chechen fighters were subsequently detained, tortured, and killed.

The materials of the Database show the large-scale use of torture as a method of warfare.

The statistics provided were updated until 11 April 2019.

The data is subject to change in view of the ongoing work by the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center on the search and identification of victims of the armed conflict.

Audio library

Listen to the story of a refugee from Alkhan-Kala concerning the “sweeping operation” in the village.

For details on this story, see the “Audio” section.

Media library

NEDC document 27970

NEDC document 28607

NEDC document 23851

NEDC document 26550

NEDC document 28607

NEDC document 28607

References

[1]The Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center Project uses the definitions of civilian population and combatants/irregular fighters depending on the degree of involvement of the population in hostilities, based in the context of the non-international armed conflict in Chechnya.

[2]The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, December 10, 1984, Article 1. Also, see the interpretation of Article 1 in the International Journal of the Red Cross, «In truth the leitmotiv …»: prohibition of torture and other forms of ill-treatment international humanitarian law. (C. Droege), volume 89, No. 867, September 2007, https://www.icrc.org/ru/doc/resources/documents/article/review/review-867-p515.htm.

[3]See, for example, the International Committee of the Red Cross, «Prohibition and Punishment of torture and other forms of ill-treatment», June 2014, https://www.icrc.org/ru/doc/assets/files/2014/141443_ru_torture_factsheet_ru%5b1%5d.pdf.

[4]«Chechen President Recognizes the Use of Torture in the Republic», Nezavisimaya Gazeta, March 1, 2006.

[5]The Database mainly contains information about violations committed during the period of the second armed conflict that started in 1999. However, it also contains sporadic facts recorded during the first armed conflict.

[6]Victim № № 65531, 67287.

[7]Incident № 312 «Incidents in Goy-Chu (Komsomolskoye), March 2000».

[8]Incident № 492 «Detention conditions of detainees, 1999-2000».

[9]Document № 1653.

[10]Document № 1653.

[11]It is worth noting that, unlike their role and belonging, the status of a person during a conflict could vary depending on certain circumstances. Due to the fact that the focus of this publication is the torture of combatants, these statistics do not include employees of local and federal law enforcement agencies who were not in the line of duty (NISO) and were not combatants at the time of the violation. There are eight such victims.

[12]Incident № 312 « Incidents in Goy-Chu (Komsomolskoye), March 2000».

[13]Incident № 312 «Incidents in Goy-Chu (Komsomolskoye), March 2000».

[14]Incident № 492 «Detention conditions of detainees, 1999-2000».

[15]Document № 27577.

[16]Incident № 942 «Detention and murder of civilians in the city Shali, March 2000».

[17]Document № 1653.

[18]Document № 1653.

[19]Incident № 4635 «Killing of G-v in Alkhan-Yurt, 2000».

[20]Victim № 60655.

[21]Victim № 63408.

[22]Victim № 45554.

[23]Incident № 164 «Kidnapping of Chechen policemen in Grozny, 16 (17) July 2000».

[24]Victim № 59017.

[25]Victim № 54022.

[26]Victim № 57404.