Death and injuries as a result of mine explosions

International humanitarian law is aimed “primarily at reducing the suffering caused by armed conflicts”,[1] and also to regulate and limit the choice of weapons of the conflicting parties. At the end of the 20th century, the widespread international campaign to ban the use of various types of mines[2] increased international awareness on the dangers of such weapons. According to the former UN Secretary-General, Mr. Kofi Annan:

“Landmines are cruel instruments of war. Decades after conflicts have receded, these invisible killers lie silently in the ground, waiting to murder and maim.”[3]

While some types of mines are successfully regulated and prohibited by international conventions, the use of other types of weapons continues to take the lives of civilians and cause irreparable damage to the environment.

The Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center Database (hereinafter the Database) has registered information relating to at least 139 cases on the use of anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines as well as booby-traps used in the conflict in the North Caucasus.[4] The overwhelming majority of incidents (123 cases) occurred in the Chechen Republic.

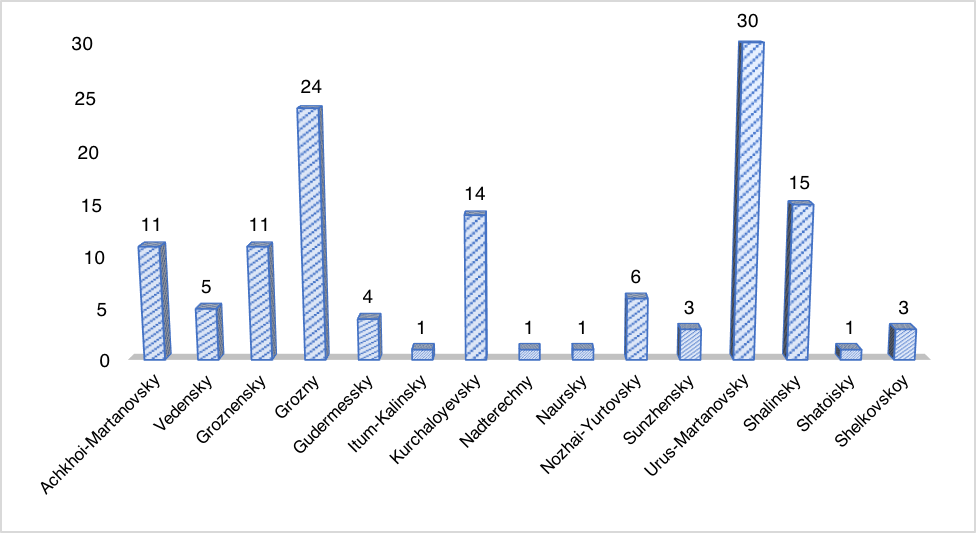

The geographical distribution of the explosions is relatively even, with the exception of the sharply distinguished locations of the Urus-Martanovsky District (30 incidents) and Grozny (24 incidents) (see chart 1).[5]

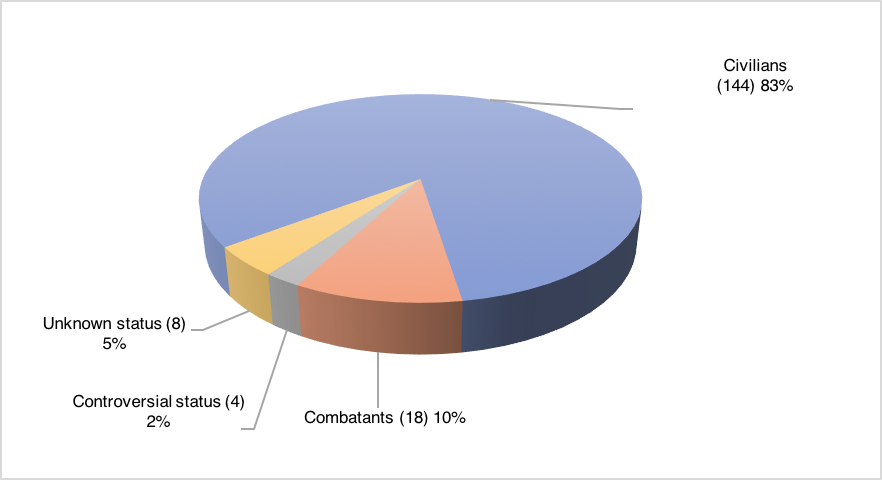

Thus, at least 174 people were killed in the Chechen Republic as a result of mine explosions. 144 of the victims (or 83%) were civilians and 18 were combatants (see chart 2). The status of a further 12 victims is either unknown or unclear. Furthermore, 162 of the victims were men and 12 were women. Slightly less than one third of all the victims (47 victims) were minors; with 20 being children under the age of 14 and the remaining 27 being between the ages 14 and 17. Children and teenagers who played or worked together would often be struck by mines and were killed, or if they survived were seriously maimed. For example, on 28 August 2000, a 15-year-old boy and his 11-year-old sister had travelled to the outskirts of their village Ushkaloy in the Itum-Kalinsky District to tend to the cows from the pasture when a mine was detonated near them. The girl died immediately and the boy lost his arm and was taken to hospital.[6]

Other victims of mine explosions belonged to vulnerable groups such as: the elderly (11 victims); internally displaced persons (six victims); those in a helpless state (three victims); and those with disabilities (one victim). The total number of such victims amounts to 64 individuals, including children.

The Database lists forests, streets, urban and rural squares, gardens, victims’ houses and even schools and cemeteries as locations of mine explosions in cities and villages in the Chechen Republic. Due to the poor financial situation caused by the conflict in the region, surrounding forests held important economic significance for the civilian population. As a result, the Database has registered information relating to at least 13 cases whereby victims were killed by mines while harvesting firewood or collecting wild garlic in the forest. One such example occurred on 6 March 2006 in the village of Dzhugurty in the Kurchaloyevsky District, when several locals were hit by an exploding mine whilst gathering wild garlic; two of the victims were killed and one was seriously injured.[7] Despite warnings issued by the authorities,[8] individuals would nevertheless risk their lives and travel to forests due to the absence of any other financial means. However, local populations were seldom warned about the increased danger of mines within human settlements. When mines were installed by the Russian military, warning signs were often missing or were installed incorrectly. For instance, in summer 2001 during an operation in the village of Alleroy of the Nozhai-Yurtovsky District, Russian soldiers installed mines without prior warning under a bridge where local children were known to usually swim. A day after their installation, three children were struck by an exploding mine; an 11-year-old girl died from her injuries and the other two children were taken to hospital.[9] In another incident, on the western outskirts of Urus-Martan, two teenagers were killed by a mine explosion. Warning signs had been installed by Russian deminers, but were placed in a grassy area which eventually covered the sign so it was no longer visible.[10]

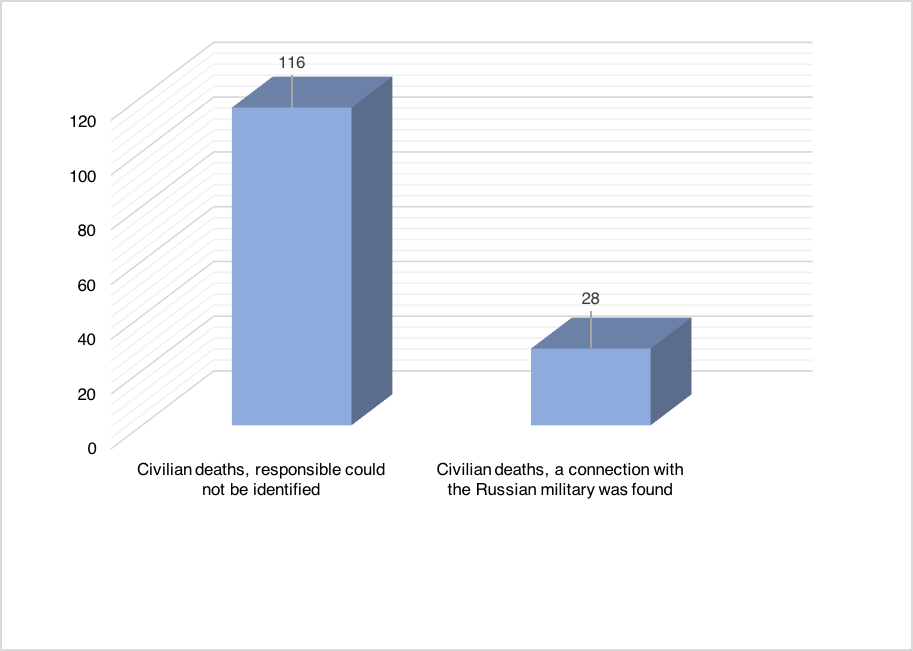

In most cases, that is 116 cases of civilian deaths, those responsible for the deployment of the mines could not be identified. However, in 28 cases, a connection with the Russian military was found (see chart 3). Mines were laid as a result of special operations that took place in populated areas or were later found in former locations of military bases. For example, on 27 March 2005 in the southern outskirts of the city of Gudermes, a local resident was hit by an exploding mine on a hill where a military unit had been previously stationed from 2000-2003. According to the testimony of local residents, no one had been engaged in the demining of the area once the military had left.[11] In another incident on 4 June 2001 in Grozny, a father and his three children were killed as a result of a mine explosion. The man had stepped on a mine while trying to fix an entrenched cross which had been installed by the Russian military in memory of their deceased colleagues. According to relatives, the military had previously threatened to blow up the victim’s house if something happened to the cross.[12]

In addition to the abovementioned fatal mine explosions, the Database has also recorded at least 45 cases in the Chechen Republic in which individuals suffered mine shrapnel injuries but survived. As a result of these injuries, the quality of life of the victims was vastly impaired following the incidents. Some victims were injured at a very young age. For instance, on 25 August 2001 in the village of Alleroy of the Kurchaloyevsky District, a 16-year-old boy stepped on a mine which exploded in the yard of his own house. Due to the sweeping operation (zachistka) carried out in the village at the time, local residents were unable to rescue the boy for fear of stepping on mines themselves, and the teenager was forced to lay on the ground, bleeding, until the evening. According to eyewitnesses, the military “stood aside and chuckled, watching the young boy in pain.”[13]

As for mines used for tactical purposes, registered incidents in the Database mention anti-transport, anti-tank, and anti-personnel mines, as well as so-called booby-traps or surprise mines. The vast majority of victims (165 victims) died as a result of the use of anti-personnel mines or booby-traps. The use of anti-vehicle and anti-tank mines was identified in the minority of documented incidents. One such example was the explosion of a bus on 3 October 2000 near the bridge crossing the Argun River. As a result of the explosion, three victims (including a young teacher) who happened to be at the river collecting water were killed and two victims were injured.[14]

So-called booby-traps or surprise mines were often disguised as everyday household items and thus would mistakenly attract the attention of locals, including children. For instance, on 13 December 2003, a seven-year-old girl was taken to hospital in Grozny with an injury resulting from an exploding mine. The cause of the explosion was a booby-trap disguised as a lighter which the girl found on the street. According to the mother:

When I ran into the next room, I saw A.: she was covered in blood. At that moment, my brother ran in (he was in the courtyard). He grabbed A. and did not let me in, but I saw that she had no hands and no left eye. In the district hospital, where A. received medical care, the doctors told us that this is the third case in the district when people pick up a lighter on the street, and once they try to use it, it explodes.[15]

The use of booby-traps is strictly regulated under international humanitarian law. Disguising explosive devices under seemingly safe everyday objects violates the basic principles of differentiation and causes unnecessary suffering of the civilian population.[16] It is worth noting that in addition to lighters, the Database includes cases where explosive mines were disguised as plates,[17] kettles[18] and video tapes.[19]

The use of various kinds of mines was widespread during the conflict in the North Caucasus and resulted in the suffering of a large number of civilians. The danger of this type of weapon lasts for many years and threatens the safety of the civilian population in the Chechen Republic.

The statistics provided have been revised and verified up until 16 April 2019.

The data is subject to change in view of the ongoing work by the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center on the search and identification of victims of the armed conflict.

Audio library

Listen to the witness’s account of the death of her nephew due to a mine explosion and the death of her uncle.

For details on this story, see the “Audio” section.

Media library

NEDC document 29624

NEDC document 29624

NEDC document 29624

NEDC document 31560

NEDC document 29260

NEDC document 32091

References

[1]Review of the International Red Cross, «Weapon», dated 29.10.2010, https://www.icrc.org/ru/doc/war-and-law/weapons/overview-weapons.htm.

[2]Article 2 of the Protocol for the Prohibition or Restriction of the Use of Mines, booby-traps and other devices (Protocol II, as amended on 03.05.1996) defines mines as «munition placed under, on or near the ground or other surface area and designed to be detonated or exploded by the presence, proximity or contact of a person or vehicle».

[3]A message from the former Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, on the occasion of the International Mine Awareness Day, dated 04.04.2006, UN, http://www.un.org/ru/sg/annan_messages/2006/demining06.shtml.

[4]The Database mainly contains information about violations committed during the period of the second armed conflict that started in 1999. However, it also contains sporadic facts recorded during the first armed conflict.

[5]In the areas missing in the schedule (Argun, Galanchzhosky and Sharoysky Districts) no mine explosions were registered in the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center Database. In addition, four incidents in the Database are marked geographically under “Famous Landmarks”. This means that there is information about a specific landmark in relation to the incident, however, the area has not been specified (for example, the incident occurred along the route of the federal highway Kavkaz «M29»).

[6]Incident № 5619 «Explosion of brother and sister on a mine in the village of Ushkala, August 2000».

[7]Incident № 3142 «Explosion of residents of the village of Dzhugurty on a mine, March 2006».

[8]For example, document № 17263 «Mine danger in the forests, the insecurity of the Maysky village in the Chechen Republic, the growth of the economy of the Republic of Ingushetia», says that the military commander of one of the Chechen districts addressed the population through a district newspaper asking them to refrain from hiking in the forest because of increased mine danger.

[9]Incident № 315 «Explosion of children on a mine in of Alleroy, August 2001».

[10]Incident № 5610 «Explosion of brothers on a mine in the city of Urus-Martan, November 2000».

[11]Incident № 5676 «Explosion of D. on a mine in the city of Gudermes, March 2005».

[12]Incident № 5617 «Explosion of S. on a mine in Grozny, June 2001».

[13]Document № 8353.

[14]Incident № 5622 «Explosion of a bus on a mine near Chiri-Yurt, October 2000».

[15]Document № 3009 «Injured as a result of explosion of a lighter».

[16]Protocol on the prohibition or restriction of the use of mines, booby-traps and other devices (Protocol II to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons of 10.10. 1980), Art. 3 (3), (7), (8), (10), 6 (1), 7 (1).

[17]Incident № 5642 «Explosion of M. on a mine in the village of Shuani, August 2000».

[18]Incident № 5680 «Explosion of two sisters on a mine in Grozny, April 2000».

[19]Incident № 5696 «Explosion of M. on a mine in Kurchaloy, October 2000».