Victims in search of justice

This publication focuses on the numerous attempts by civilians – who were victims of the military conflict in Chechnya – to obtain justice for the killings and disappearances of their families and loved ones. Unfortunately, only a small number managed to obtain justice at an international level – for example, at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) – and even fewer obtained justice at the national level, that is, before Russian domestic institutions.

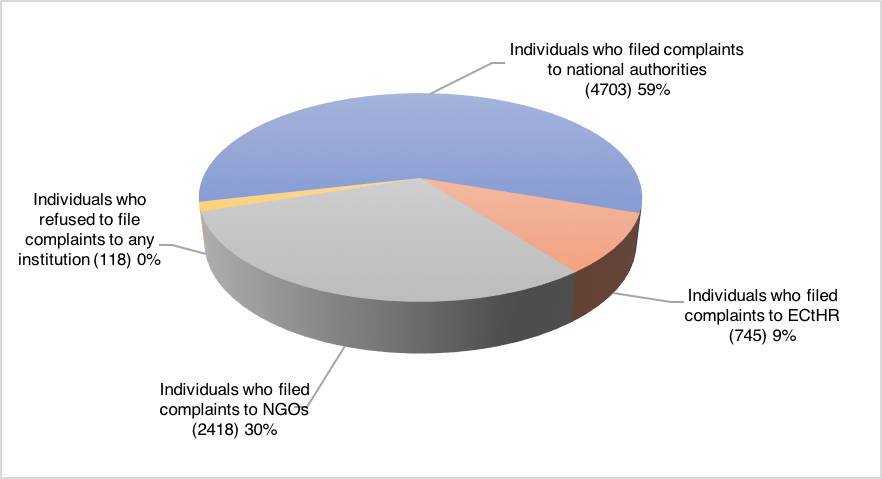

Based on information in the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center Database (hereinafter the Database), it has been established that at least 4,703 individuals[1] filed complaints regarding various crimes of a military nature to national authorities, namely, the investigating authorities or the prosecutor’s office (see chart 1). At least 2,418 individuals submitted applications to non-governmental human rights organizations, such as the Memorial Human Rights Centre.

At least 745 individuals lodged complaints concerning the actions (or inaction) of Russian law enforcement bodies to the ECtHR. A further 118 individuals refused to apply or file complaints to any institution, citing a lack of results or the ineffectiveness of the investigation procedure as the main reason for this. Others did not file complaints due to threats received and fear for their own and their relatives’ lives.

At least 3,745 criminal cases were opened in response to such complaints. While this number may appear substantial, it must be emphasized that in relation to at least 1,352 cases the investigation was either suspended, terminated or not brought before the court. In the remaining cases, the status of the investigation remains unknown. The majority of the criminal proceedings opened related to the killing or disappearance of at least 3,119 victims.

According to available information, only four criminal trials have been conducted against the perpetrators of outrageous crimes committed against civilians (including murder, disappearances and torture). The following cases gained great publicity in the Russian media: the case of Colonel Yuri Budanov;[2] the case of Sergey Lapin (Cadet);[3] the case of Ulman;[4] and the case of Akarcheev and Khudyakov.[5]

In 2003, Mr. Budanov, a former commander of a tank regiment, was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment following his conviction for killing 18-year-old Elza Kungaeva in 2001. In 2009, he was released on parole. In 2011, he was shot dead in Moscow.[6]

Sergey Lapin, a police officer of the Khanty-Mansiisk Autonomous District, who served in Chechnya in 2000-2001, was convicted of torturing and killing a local resident, 26-year-old Zelimkhan Murdalov. Zelimkhan’s body was never found. As a result of the final trial in 2007, Lapin was sentenced to 10 years and six months in prison. In 2011, the Supreme Court reduced the sentence to 10 years. He was released in 2014.[7] It is noteworthy that in relation to two other accomplices who have been wanted by the police for many years, Lieutenant Colonel Minin and Major Prilepin, the criminal case against them was terminated in 2016. Amnesties apply to both individuals.[8]

Mr. Eduard Ulman, captain of the GRU special forces, was convicted of shooting six civilians who were mistakenly identified as fighters, close to the village of Dai in 2002. The car in which the civilians were travelling was stopped by Ulman’s subordinates. Among the passengers was a pregnant woman. All the passengers were shot and their corpses along with the car were set on fire.[9] Ulman’s subordinates, which included Lieutenant Kalagansky, warrant officer Vojevodin and Major Perelevsky – the latter being the one who had ordered the execution – were acquitted during the first three trials. However, in 2007, the North Caucasian District Military Court in Rostov-na-Donu sentenced Perelevsky to nine years’ imprisonment. The remaining individuals were convicted in absentia, as prior to the announcement of the verdict they had been subject to a written undertaking prohibiting them from leaving the town, and soon after they went missing.[10] Ulman was sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment.

Lieutenant Akarcheev and Senior Lieutenant Yevgeny Khudyakov were accused of killing three civilians from the village of Laha-Varanda in Grozny in 2003. They were acquitted by a jury twice, but in 2007 they were sentenced to 15 (Akarcheev) and 17 (Khudyakov) years’ imprisonment. Khudyakov, like Ulman, did not appear at the sentencing hearing and was subsequently placed on a wanted list. It was only in 2017 that Khudyakov was detained.[11] In 2016, Akarcheev was released on parole.

It is worth noting that while the Russian authorities accused and convicted several people for the commission of kidnappings and killings, the investigating authorities also accused at least 445 suspects – who were residents of Chechnya – for crimes of a terrorist nature.

The Database contains information on at least 438 criminal cases initiated on various grounds, as well as on civil cases relating to compensation for material damage suffered as a result of unlawful actions by security forces (for example, those committed during sweeping operations (zachistkas)). In 105 of these cases (both criminal and civil), investigators conducted some investigative actions, such as crime scene investigations (in 23 cases), interrogations (in 79 cases), forensic examinations (in 10 cases), and other procedural actions. Information on these cases is limited due to the fact that materials relating to criminal and civil cases are only made available to a limited number of people.

As reflected in the statistics, the investigation of numerous offenses did not lead to effective results at a national level. Thus, residents of Chechnya were not left with many options to seek effective remedies to protect their rights and the rights of their relatives. As a result, many of them turned to the ECtHR in Strasbourg in search of justice. It is important to note that the violations recognized by the Court are declarative in nature, and it is not the task of the Court to identify the perpetrators responsible. The investigation and identification of the perpetrators and their punishment remains the prerogative and obligation of the State against which the judgment is imposed. Thus, even in cases where the Court finds Russia responsible for the violation of human rights during the Russian-Chechen conflict, Russia has the obligation to thoroughly investigate the circumstances of the violation, including bringing to justice those who committed the crimes.

The first judgments in which the Court found the Russian Federation in violation of human rights were the cases of Isayeva, Yusupova and Bazayeva v. Russia; Isayeva v. Russia; and Khashiev and Akayeva v. Russia.[12] The first case concerned the aerial shelling of a convoy of refugees as well as an International Red Cross convoy on 29 October 1999 on the federal highway “Caucasus” near the village of Shaami-Yurt. During the incident two children from Medka Isayeva were killed and the lives of two other applicants, Zina Yusupova and Libkan Bazayeva, were endangered. During the shelling, at least 25 people were killed and more than 70 injured.[13]

In the second case, the Court found a violation during the shelling of the village of Katyr-Yurt on 4 February 2000, when the son and three nieces of the applicant were killed. In addition, the shelling led to the death of at least 46 individuals, all of whom were civilians, and caused injuries to 50 others.[14]

The case of Khashiyev and Akayeva v. Russia, as well as many other cases in which the Court found a violation of the right to life, concerned extrajudicial killings of people. In the case of Magomed Khashiyev, the applicant’s brother, sister, and two nephews were found wounded in Grozny in January 2000 with numerous gunshots. Rosa Akayeva also found her brother dead among the victims of the attack. The fact that the murder was committed by military personnel was not disputed during the investigation; however, the perpetrators were never found. The Court once again confirmed the conclusion of the national authorities and found Russia responsible for the violation of the right to life of the applicants’ relatives.

In subsequent cases, on many occasions the Court found Russia responsible for the violation of the right to life of the applicants’ relatives as a result of killings committed by the military. For example, in the cases of Musayev and Others v. Russia; Musaev v. Russia; and Khadzhimuradov and Others v. Russia, the applicants filed their complaints following the massacre of civilians on 5 February 2000 in the village of Novye Aldy, including the killing of the applicants’ relatives by military personnel.[15] At least 60 people were shot in the streets and in their own houses.[16]

In a number of other cases, the Court also found violations during the shelling of the village of Kogi on 12 September 1999,[17] of the village of Znamenskoe on 5 October 1999,[18] and of the city of Urus-Martan on 2 and 19 October 1999.[19]

Furthermore, relatives of those who had disappeared also appealed to the Court in relation to the kidnappings of their close relatives by the military. In many cases, Russia was found responsible for the actions of the military.[20] In some cases, due to inadequate investigation at the national level, the responsibility of the security forces could not be established. In such cases, the Court could not establish the fact of kidnapping or killing by the security forces and thus found no violation of the right to life in relation to its material aspects. Nevertheless, the Court found a violation of the procedural aspects of the right to life under the Convention, meaning that the investigating authorities had not conducted an investigation capable of establishing the circumstances of the violation, as well as the perpetrators.[21]

As already mentioned, relatives of at least 789 victims filed complaints with the ECtHR. It is known that in respect of at least 574 victims, the Court found various violations. In respect of at least 70 people, the Court found a partial violation of rights. These include the cases described in the previous paragraph. With regard to the remaining victims, information is not yet available as the Court is still in the process of examining complaints in cases related to the military conflict in Chechnya.

The statistics provided have been revised and verified until 18 April 2019.

The data is subject to change in view of the ongoing work by the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center on the search and identification of victims of the armed conflict.

Media library

NEDC document 27970

NEDC document 10503

NEDC document 9861

NEDC document 25891

NEDC document 27970

NEDC document 27970

References

[1]The Database mainly contains information about violations committed during the period of the second armed conflict that started in 1999. However, it also contains sporadic facts recorded during the first armed conflict. The statistics do not include residents of Chechnya who had been abducted in neighboring regions, as well as residents of Ingushetia, Dagestan and other republics of the North Caucasus, who have been victims of the armed conflict in Chechnya.

[2]«Budanov case: the colonel was drunk», RBC.ru, https://www.rbc.ru/politics/10/05/2001/5703b2539a7947783a5a1bfe; «The case of Colonel Budanov. Are the results of the examination convincing, recognizing commander of a tank regiment deranged?», Svoboda.org, https://www.svoboda.org/a/24199535.html.

[3]«The case of the officer of the Khanty-Mansiysk OMON Sergei Lapin», Svoboda.org, https://www.svoboda.org/a/24185575.html; «Is the case over?», Echo Kavkaza, https://www.ekhokavkaza.com/a/27465428.html; «Lawyer Markelov: colleagues of “Cadet” are afraid of sharing responsibility with him», Kavkaz Uzel, https://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/126825/.

[4]«Can captain Ulman be tried by the Court?», Novaya Gazette, https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2006/05/29/29122-podsuden-li-kapitan-ulman; «Case of Ulman, take three», Gazeta, https://www.gazeta.ru/politics/2006/06/07_kz_657081.shtml.

[5]«Khudyakov convicted of killing Chechens was detained 10 years after conviction», BBC, https://www.bbc.com/russian/news-41553941; «Case of Arakcheeva and Khudyakova», OVD, https://ovdinfo.org/story/delo-arakcheeva-i-hudyakova.

[6]Incident № 210 «The case of Yuri Budanov, 2000 – 2003».

[7]«The Cadet case. Torture and death of the Chechen Murdalov», On Kavkaz, https://onkavkaz.com/news/610-delo-kadeta-pytki-i-smert-chechenca-murdalova.html.

[8]Incident № 214 «The case of Sergey Lapin, 2001-2007».

[9]Incident № 430 «The killing of civilians in Dai, January 11, 2002».

[10]«Out in deep intelligence: The three defendants in the case of Ulman were missing», Lenta.ru, https://lenta.ru/articles/2007/04/16/ulman/.

[11]«Khudyakov convicted of killing Chechens was detained 10 years after conviction», BBC, https://www.bbc.com/russian/news-41553941.

[12]«Isaeva, Yusupova and Bazayeva v. Russia” (Application No. 57947/00 and two others); Isayeva v. Russia (Application No. 57950/99); Khashiev and Akayeva v. Russia (Application No. 57942/00, 57945/00), February 24, 2005.

[13]Incident № 267 «The death and injury of citizens during rocket attack at Shaami-Yurt, October 29, 1999».

[14]Incident № 156 «Special operation in Katyr-Yurt, February 2000».

[15]«Musaev and Others v. Russia (Appl. No. 57941/00 and two others), July 26, 2007; Musayeva v. Russia (Application No. 12703/02); Khadzhimuradov and Others v. Russia (Application No. 21194/09 and 16 others).

[16] Incident № 271 «Zachistka in Novye Aldy, February 5, 2000»; Report «Russia/Chechnya, February 5: A Day of Slaughter in Novye Aldi», Human Rights Watch, 1 June 2000, https://www.hrw.org/report/2000/06/01/russia/chechnya-february-5-day-slaughter-novye-aldi; «Stripping». Novye Aldy, February 5, 2000 – Deliberate Crimes Against Civilians, February 10, 2010», Kavkaz Uzel, https://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/165295/; «Novye Aldy: it will not be possible to forget», July 30, 2007, Novaya Gazeta, https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2007/07/30/32530-novye-aldy-zabyt-ne-udastsya.

[17]«Esmukhambetov and Others v. Russia» (Application No. 23445/03), March 29, 2011.

[18]«Mezhidov v. Russia» (application No. 67326/01), September 25, 2008.

[19]«Kerimov and Others v. Russia» (Application No. 17170/04 and 5 others), May 3, 2011.

[20]For example, «Umarov and Others v. Russia» (Application No. 25654/08), July 31, 2012; «Gakayeva and Others v. Russia» (Application No. 51534/08 and 9 others), October 10, 2013; «Petimat Ismailova v. Russia» (Application No. 25088/11 and 11 others), September 18, 2014; «Sultygov and Others v. Russia» (Application No. 42575/07), October 9, 2014; «Ortsueva and Others v. Russia» (Application No. 3340/08 and 24689/10), November 22, 2016, and many other cases.

[21]For example, «Tsechoev v. Russia» (Application No. 39358/05), March 15, 2011; «Kharayeva and Others v. Russia» (Application No. 2721/11), November 27, 2014; «Bimuradova v. Russia» (Application No. 3769/11), November 12, 2015; «Kagirov against Russia» (Application No. 36367/09), April 23, 2015, and many other cases.